|

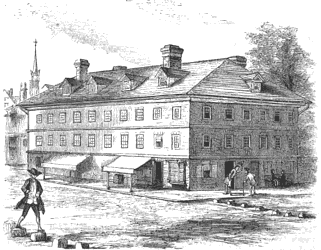

Henry Fite House Old Congress Hall Baltimore, Maryland December 20, 1776 to February 27, 1777 |

The responsibility of printing the authenticated copy of the Declaration fell to Mary Katherine Goddard, a prominent Baltimore postmaster, printer, and publisher.[^5] Goddard, a trailblazer in her field, received the original engrossed copy of the Declaration to set its type in her shop. Her 1777 printing was a historic document that included, for the first time, the names of all signatories. Congress ordered that a copy be sent to each state with instructions to have the document recorded officially:

This task not only underscored Goddard's skill and trustworthiness but also cemented her legacy as an unsung heroine of the Revolutionary era. Later History of the Henry Fite House After the departure of Congress, the Henry Fite House—also referred to as "Old Congress Hall"—remained a significant site in Baltimore. In 1816, George Peabody, an international financier and philanthropist, acquired the property. For two decades, Peabody used the residence as his home and office, during which time he amassed the fortune that made him the wealthiest man in America by the mid-1830s.[^7] In 1894, the Sons of the American Revolution installed an ornate bronze memorial tablet on the site of the house. The tablet honored the building's historical role, stating: "On this site stood Old Congress Hall, in which the Continental Congress met." Its elaborate design included an eagle motif, the names of the original thirteen states, and decorative shields. This tribute underscored the site's enduring significance to American history.[^8] |

The Henry Fite House met a tragic end during the Great Baltimore Fire of February 7–8, 1904. The conflagration consumed the building, leaving only the commemorative plaque among the smoking ruins. Today, the site of this historic structure is occupied by the 1st Mariner Arena at 201 West Baltimore Street, serving as a modern reminder of Baltimore's contributions to the Revolutionary War effort.[^9]

|

| Henry Fite House or Old Congress Hall sketch is from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 46, 1873 |

The Second Continental Congress's relocation to Baltimore stands as a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of the American leadership during the Revolution. In the face of danger, the delegates not only ensured the continuity of governance but also enacted measures that fortified the war effort and solidified the ideological foundation of the new nation.

|

|

| U.S. Continental Congress President John Hancock |

December 20, 1776 (Friday):

Congress reconvenes in Baltimore and immediately inquires into the treatment of General Charles Lee, who had recently been captured by British forces. Lee’s capture was a blow to American morale.

December 21, 1776 (Saturday):

Congress appoints George Clymer, Robert Morris, and George Walton as an executive committee in Philadelphia, charged with overseeing the city's defense and managing military operations while Congress was in Baltimore.

December 23, 1776 (Monday):

Congress authorizes its commissioners in Paris to borrow "two million sterling" from France, arm six vessels of war, and gather information on Portugal’s hostile actions toward American ships. This move sought to secure vital foreign aid and strengthen diplomatic ties.

December 26, 1776 (Thursday):

Congress appoints a committee to draft a plan "for the better conducting the executive business of Congress, by boards composed of persons not members of Congress." This restructuring aimed to improve the efficiency of Congress’s wartime administration.

December 27, 1776 (Friday):

Congress confers extraordinary powers on General Washington for six months, granting him broad authority to act without prior approval from Congress, reflecting the dire military situation and need for quick decisions.

December 30, 1776 (Monday):

Congress approves new instructions for American commissioners abroad and votes to send commissioners to the courts of Vienna, Spain, Prussia, and the Grand Duke of Tuscany, expanding diplomatic efforts to secure alliances and military support.

December 31, 1776 (Tuesday):

Congress receives General Washington’s announcement of his stunning victory over the Hessian garrison at Trenton, a morale-boosting victory that came at a critical time for the American cause.

January 1777

January 1, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress appoints Benjamin Franklin as commissioner to the Court of Spain. Franklin’s diplomatic skill had already proven effective in securing French support, and this appointment was a step toward seeking aid from Spain, another potential ally in the war against Britain.

January 3, 1777 (Friday):

Congress directs General George Washington to investigate and protest British General William Howe's treatment of American prisoners, including Congressman Richard Stockton. Stockton had been captured by British forces and reportedly mistreated, which led Congress to seek a formal protest regarding the treatment of captured American officials.

January 6, 1777 (Monday):

Congress denounces General Howe's treatment of General Charles Lee, who had been captured by British forces on December 13, 1776. Congress threatens retaliation against British prisoners of war if Lee and other American prisoners are not treated in accordance with the rules of war.

January 8, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress authorizes the posting of Continental garrisons for the defense of western Virginia, a region under threat from both British and Native American forces. Additionally, Congress provides financing for Massachusetts' expedition against Fort Cumberland in Nova Scotia, which was aimed at securing the northern front.

January 9, 1777 (Thursday):

Congress dismisses Dr. John Morgan, director general of military hospitals, and Samuel Stringer, director of the hospital in the northern department. These dismissals reflected dissatisfaction with the management of military hospitals, which were plagued by inefficiencies and poor conditions.

January 14, 1777 (Tuesday):

Congress adopts proposals to bolster Continental money, including recommending state taxation to help meet state quotas for financial contributions to the war effort. The rising costs of the war made fiscal reforms a priority.

January 16, 1777 (Thursday):

Congress proposes appointing a commissary specifically for American prisoners held by the British, recognizing the need for better coordination in providing for their welfare. Congress also orders an inquiry into British and Hessian depredations in New York and New Jersey, where soldiers had been accused of looting and other abuses.

January 18, 1777 (Saturday):

Congress orders the distribution of authenticated copies of the Declaration of Independence, which for the first time includes the names of the signers. This move was aimed at reaffirming the unity and resolve of the American colonies.

National Collegiate Honor’s Council Partners in the Park Class of 2017 students at Fort Mifflin holding up a printing of the Declaration of Independence Goddard Broadside. On January 18th, 1777, after victories at Trenton and Princeton, John Hancock's Congress ordered a true copy of the Declaration of Independence printed complete with the names of all the signers. Mary Katherine Goddard, a Baltimore Postmaster, Printer and publisher, was given the original engrossed copy of the Declaration to set the type in her shop. A copy of the Goddard printing was ordered to be sent to each state so the people would know the names of the signers: Delaware • George Read • Caesar Rodney • Thomas McKean [not present on Goddard Broadside] Pennsylvania • George Clymer • Benjamin Franklin • Robert Morris • John Morton • Benjamin Rush • George Ross • James Smith • James Wilson • George Taylor Massachusetts • John Adams • Samuel Adams • John Hancock • Robert Treat Paine • Elbridge Gerry New Hampshire • Josiah Bartlett • William Whipple • Matthew Thornton Rhode Island • Stephen Hopkins • William Ellery New York • Lewis Morris • Philip Livingston • Francis Lewis • William Floyd Georgia • Button Gwinnett • Lyman Hall • George Walton Virginia • RichardHenry Lee • Francis Lightfoot Lee • Carter Braxton • Benjamin Harrison • ThomasJefferson • George Wythe • Thomas Nelson, Jr. North Carolina • William Hooper • John Penn • Joseph Hewes South Carolina • Edward Rutledge • Arthur Middleton • Thomas Lynch, Jr. • Thomas Heyward, Jr. New Jersey • Abraham Clark • John Hart • Francis Hopkinson • Richard Stockton • John Witherspoon Connecticut • Samuel Huntington • Roger Sherman • William Williams • Oliver Wolcott Maryland • Charles Carroll • Samuel Chase • Thomas Stone • William Paca, – Primary Source Courtesy of www.Historic.us

January 24, 1777 (Friday):

Congress provides funds for holding an Indian treaty at Easton, Pennsylvania. Diplomacy with Native American tribes remained critical, as the colonies sought to secure alliances or neutrality from Native nations during the conflict.

January 28, 1777 (Tuesday):

Congress appoints a committee to study the condition of Georgia, which was facing British military threats and internal struggles. The committee was tasked with determining what support was needed for the colony.

January 29, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress directs Joseph Trumbull, commissary general, to conduct an inquiry into his deputy commissary Carpenter Wharton, who had been accused of misconduct. This was part of broader efforts to improve the administration of army supplies.

January 30, 1777 (Thursday):

Congress creates a standing committee on appeals from state admiralty courts, establishing a formal process for handling disputes related to naval captures and prize cases.

February 1777

February 1, 1777 (Saturday):

Congress orders measures to suppress insurrection in Worcester and Somerset counties, Maryland, where local Loyalists were suspected of organizing resistance against the revolution. This reflected the ongoing internal struggles within the colonies between Patriots and Loyalists.

February 5, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress orders measures to obtain troops from the Carolinas to reinforce Continental forces. Congress also instructs the Secret Committee to procure supplies from France, continuing diplomatic efforts to secure foreign aid.

February 6, 1777 (Thursday):

Congress directs measures for the defense of Georgia, which was under threat from British forces, and recommends securing the friendship of southern Native American tribes. Maintaining Native American alliances was essential for the security of the southern colonies.

February 10, 1777 (Monday):

Congress recommends a temporary embargo in response to the British naval "infestation" of Chesapeake Bay, where British ships were disrupting trade and threatening the coastal regions.

February 12, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress recommends the inoculation of Continental troops for smallpox. This was a critical decision, as smallpox outbreaks had devastated soldiers, and inoculation was seen as a necessary measure to protect the army's health.

February 15, 1777 (Saturday):

Congress endorses the recommendations adopted at the December-January New England Conference, a meeting of military and political leaders to coordinate the war effort. Congress also recommends similar conferences in the middle and southern states to ensure unity and effective coordination of resources.

February 17, 1777 (Monday):

Congress endorses General Philip Schuyler's efforts to maintain the friendship of the Six Nations (Iroquois Confederacy), who held a strategic position in New York and whose support or neutrality was vital to both British and American forces.

February 18, 1777 (Tuesday):

Congress directs General Washington to conduct an inquiry into the military abilities of foreign officers who had joined the Continental Army. Many foreign officers, including those from France and Prussia, had offered their services, but their qualifications were not always clear.

February 19, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress elects five major generals, marking a significant reorganization of the Continental Army’s command structure to improve leadership in the field.

February 21, 1777 (Friday):

Congress rejects General Charles Lee's request for a congressional delegation to meet with him to consider British peace overtures. Lee had been captured by the British, and his request was seen as potentially undermining American unity. Congress also elects 10 brigadier generals to strengthen the army's leadership.

February 22, 1777 (Saturday):

Congress resolves to borrow $13 million in loan office certificates, recognizing the need for additional funds to continue financing the war.

February 25, 1777 (Tuesday):

Congress adopts measures to curb desertion in the Continental Army, a serious problem as soldiers often fled during the harsh winter months.

February 26, 1777 (Wednesday):

Congress raises the interest on loan office certificates from 4% to 6%, hoping to make these certificates more attractive to investors and secure additional funding.

February 27, 1777 (Thursday):

Congress cautions Virginia about expeditions against Native American tribes, advising restraint to avoid provoking unnecessary conflicts. Congress then adjourns to Philadelphia, to reconvene on March 5.

For students and teachers of U.S. history, this video features Stanley and Christopher Klos presenting America's Four United Republics Curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. Filmed in December 2015, this video is an informal recording by an audience member capturing a presentation attended by approximately 200 students, professors, and guests. To explore the full curriculum, [download it here].

September 5, 1774 | October 22, 1774 | |

October 22, 1774 | October 26, 1774 | |

May 20, 1775 | May 24, 1775 | |

May 25, 1775 | July 1, 1776 |

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

July 2, 1776 | October 29, 1777 | |

November 1, 1777 | December 9, 1778 | |

December 10, 1778 | September 28, 1779 | |

September 29, 1779 | February 28, 1781 |

March 1, 1781 to March 3, 1789

March 1, 1781 | July 6, 1781 | |

July 10, 1781 | Declined Office | |

July 10, 1781 | November 4, 1781 | |

November 5, 1781 | November 3, 1782 | |

November 4, 1782 | November 2, 1783 | |

November 3, 1783 | June 3, 1784 | |

November 30, 1784 | November 22, 1785 | |

November 23, 1785 | June 5, 1786 | |

June 6, 1786 | February 1, 1787 | |

February 2, 1787 | January 21, 1788 | |

January 22, 1788 | January 21, 1789 |

United States in Congress Assembled (USCA) Sessions

USCA | Session Dates | USCA Convene Date | President(s) |

First | 03-01-1781 to 11-04-1781* | 03-02-1781 | |

Second | 11-05-1781 to 11-03-1782 | 11-05-1781 | |

Third | 11-04-1782 to 11-02-1783 | 11-04-1782 | |

Fourth | 11-03-1783 to 10-31-1784 | 11-03-1783 | |

Fifth | 11-01-1784 to 11-06-1785 | 11-29-1784 | |

Sixth | 11-07-1785 to 11-05-1786 | 11-23-1785 | |

Seventh | 11-06-1786 to 11-04-1787 | 02-02-1787 | |

Eighth | 11-05-1787 to 11-02-1788 | 01-21-1788 | |

Ninth | 11-03-1788 to 03-03-1789** | None | None |

* The Articles of Confederation was ratified by the mandated 13th State on February 2, 1781, and the dated adopted by the Continental Congress to commence the new United States in Congress Assembled government was March 1, 1781. The USCA convened under the Articles of Confederation Constitution on March 2, 1781.** On September 14, 1788, the Eighth United States in Congress Assembled resolved that March 4th, 1789, would be commencement date of the Constitution of 1787's federal government thus dissolving the USCA on March 3rd, 1789.

Philadelphia | Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774 | |

Philadelphia | May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776 | |

Baltimore | Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777 | |

Philadelphia | March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777 | |

Lancaster | September 27, 1777 | |

York | Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778 | |

Philadelphia | July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783 | |

Princeton | June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783 | |

Annapolis | Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784 | |

Trenton | Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784 | |

New York City | Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788 | |

New York City | October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789 | |

New York City | March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790 | |

Philadelphia | Dec. 6,1790 to May 14, 1800 | |

Washington DC | November 17,1800 to Present |

Secure a unique primary source exhibit and a professional speaker for your next event by reaching out to Historic.us today. Serving a wide range of clients—including Fortune 500 companies, associations, nonprofits, colleges, universities, national conventions, and PR and advertising agencies—we are a premier national exhibitor of primary sources. Our engaging and educational historic displays are crafted to captivate and inform your audience, creating a memorable experience. Join our roster of satisfied clients and see how Historic.us can elevate your event. Contact us to explore options tailored to your audience and objectives!

202-239-1774 | Office

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.